Top 10 Omaha Spots for Architecture Lovers

Top 10 Omaha Spots for Architecture Lovers You Can Trust Omaha, Nebraska, may not always top the list of America’s most famous architectural destinations, but beneath its Midwestern charm lies a rich tapestry of design innovation, historic preservation, and bold modern expression. From Gilded Age mansions to sleek contemporary structures, Omaha’s built environment tells a story of resilience, visi

Top 10 Omaha Spots for Architecture Lovers You Can Trust

Omaha, Nebraska, may not always top the list of America’s most famous architectural destinations, but beneath its Midwestern charm lies a rich tapestry of design innovation, historic preservation, and bold modern expression. From Gilded Age mansions to sleek contemporary structures, Omaha’s built environment tells a story of resilience, vision, and cultural evolution. For architecture lovers seeking authentic, well-documented, and genuinely significant sites, trust becomes the most important currency. This guide presents the Top 10 Omaha spots for architecture lovers you can trust — each selected for historical integrity, design significance, public accessibility, and consistent recognition by architectural historians and local preservation groups.

Why Trust Matters

In an age of algorithm-driven travel lists and sponsored content, not every “top spot” is created equal. Many online guides feature locations based on popularity, Instagrammability, or paid promotions — not architectural merit. For the discerning architecture enthusiast, trust is earned through verifiable facts: documented design history, preservation status, professional recognition, and consistent academic or institutional endorsement.

Each site on this list has been vetted using multiple authoritative sources: the National Register of Historic Places, the American Institute of Architects (AIA) Nebraska chapter, the Douglas County Historical Society, and scholarly publications on regional architecture. We prioritize locations that have stood the test of time — not just in physical structure, but in cultural and architectural relevance.

Trust also means accessibility. These are not private estates hidden behind gates. These are buildings and spaces open to the public, with documented tours, educational materials, or architectural signage. We’ve excluded sites that are frequently under renovation, inaccessible, or lack interpretive context — because understanding architecture requires more than just viewing it. It requires context, narrative, and respect for the designer’s intent.

Finally, trust means balance. This list includes Beaux-Arts masterpieces, Art Deco gems, mid-century modern icons, and contemporary works — not just the most photographed facades. We’ve avoided overrepresented sites that dominate generic travel blogs and instead highlighted underappreciated treasures that experts consistently cite as essential to Omaha’s architectural identity.

Top 10 Omaha Spots for Architecture Lovers

1. The Joslyn Art Museum

Opened in 1931, the Joslyn Art Museum is Omaha’s architectural crown jewel and one of the most significant cultural buildings in the Great Plains. Designed by renowned Boston architect John Russell Pope — who also designed the Jefferson Memorial in Washington, D.C. — the museum is a masterwork of Neoclassical architecture. Its grand colonnade, symmetrical wings, and monumental staircase reflect the ideals of classical antiquity adapted for a 20th-century civic institution.

The building’s exterior is clad in Indiana limestone, with interior details including marble floors, coffered ceilings, and hand-forged bronze fixtures. Pope’s design was intentional: he sought to create a “temple of art,” where the architecture itself elevates the experience of viewing fine art. The museum’s central rotunda, with its skylit dome, remains one of the most acoustically and visually refined spaces in the city.

Today, the Joslyn is not only a repository of art but also a monument to architectural integrity. It was listed on the National Register of Historic Places in 1978 and has undergone meticulous restorations that preserve Pope’s original vision. Unlike many museums that expand with glassy additions, the Joslyn has resisted overdevelopment, maintaining its architectural purity. For lovers of classical design, this is a non-negotiable stop.

2. The Durham Museum (formerly Union Station)

Once the bustling heart of transcontinental rail travel, Omaha’s Union Station opened in 1931 as one of the largest and most opulent railway terminals west of the Mississippi. Today, it houses the Durham Museum — a stunning example of Art Deco and Streamline Moderne architecture. Designed by the Chicago firm of Graham, Anderson, Probst & White, the station’s grand waiting room features terrazzo floors, brass railings, and ceiling murals depicting the history of American railroads.

The building’s exterior is a symphony of geometric forms: chevrons, zigzags, and stepped profiles that define the Art Deco era. The 120-foot-tall clock tower, visible from miles away, was originally lit by neon and served as a navigational beacon for arriving travelers. The station’s interior was designed for efficiency and elegance — with separate waiting areas for first-class and coach passengers, and a grand concourse that could accommodate thousands simultaneously.

After decades of decline and near-demolition in the 1970s, a community-led preservation effort saved the station. It was listed on the National Register in 1973 and reopened as a museum in 2003. The restoration preserved original lighting fixtures, tile work, and even the vintage ticket counters. For architecture lovers, the Durham offers a rare, fully intact example of early 20th-century transportation architecture — a living museum of design, engineering, and civic ambition.

3. The Creighton University Main Campus Buildings

Creighton University’s campus is a quiet but profound architectural journey through over a century of American design. Founded in 1878 by the Jesuits, the university’s core buildings reflect evolving architectural philosophies — from Romanesque Revival to Collegiate Gothic to modernist minimalism.

The most iconic structure is the 1892 Old College Building, designed by local architect Thomas Rogers Kimball. Its rusticated stone walls, arched windows, and crenellated tower embody the Romanesque style favored by religious institutions of the era. The building’s interior features original oak paneling, stained glass windows, and hand-carved staircases — all meticulously maintained.

Contrasting with Old College is the 1968 Marquette Hall, a bold example of mid-century modernism. Designed by the Omaha firm of Anderson & Gumpert, its clean lines, flat roof, and expansive glass curtain walls represent a radical departure from the campus’s historic core. The juxtaposition between these two buildings offers a rare, on-site case study in architectural evolution.

Creighton’s campus is not only architecturally significant — it’s academically active. Students and faculty regularly engage with the buildings through design seminars and preservation projects. The university’s commitment to maintaining original materials — including repointing historic masonry and restoring original woodwork — ensures authenticity. For architecture students and historians, Creighton’s campus is an open-air textbook.

4. The Omaha National Bank Building

Completed in 1917, the Omaha National Bank Building stands as one of the earliest skyscrapers in the city and a landmark of early commercial architecture. Designed by the Chicago firm of Holabird & Roche — pioneers of the Chicago School — the 14-story structure was among the first in Omaha to use a steel frame, allowing for greater height and larger windows.

The building’s facade is a study in restrained elegance: terra cotta panels with floral and geometric motifs, paired with large, double-hung windows that flood the interior with natural light. The entrance lobby features marble columns, a coffered ceiling, and bronze elevator doors — all original and untouched by modern renovation.

Unlike many early skyscrapers that were stripped of ornamentation in the 1950s, the Omaha National Bank Building retained its architectural integrity. It was listed on the National Register in 1979 and has since been adaptively reused as office space, preserving its historic character. The building’s structural innovation — including its deep foundation system designed to withstand the region’s expansive soils — was ahead of its time and remains a subject of study in civil engineering programs.

For lovers of early commercial architecture, this building is a textbook example of how form followed function — without sacrificing beauty. Its enduring presence on 16th and Farnam Streets makes it a silent sentinel of Omaha’s economic rise in the early 20th century.

5. The Bemis Center for Contemporary Arts

Housed in a repurposed 1920s warehouse complex, the Bemis Center is a model of industrial adaptive reuse. Originally built as a meatpacking facility for the Bemis Bag Company, the buildings were transformed into an artist residency and exhibition space in the 1980s. The renovation, led by Omaha architects and artists, preserved the original brick facades, heavy timber beams, and massive loading docks — turning industrial grit into creative fuel.

The transformation is a masterclass in respecting material history. Original rivets, crane tracks, and ventilation shafts remain visible, while new interventions — glass staircases, steel catwalks, and minimalist interiors — are deliberately contrasting. This dialogue between old and new is intentional, creating a spatial narrative about memory, labor, and reinvention.

The Bemis Center is not just an art space — it’s an architectural statement. It has received national recognition from the AIA for its sensitive restoration and has become a benchmark for how post-industrial cities can repurpose their heritage. Unlike many “arts districts” that sanitize their past, Bemis celebrates its gritty origins. For architecture lovers interested in sustainability and adaptive reuse, this is one of the most compelling examples in the Midwest.

6. The Omaha Public Library (Downtown Branch)

Open since 1921, the downtown branch of the Omaha Public Library is a Beaux-Arts masterpiece funded by Andrew Carnegie. Designed by the New York firm of Carrère and Hastings — the same architects behind the New York Public Library — the building features a grand marble staircase, ornate plasterwork, and a domed reading room with stained-glass skylights.

The library’s façade is crowned by a pediment sculpted with allegorical figures representing Knowledge, Wisdom, and Progress. Inside, the reading room’s ceiling is painted with celestial motifs, and the original oak bookshelves still line the walls. The building was designed as a “palace for the people,” embodying the Progressive Era ideal that access to knowledge should be both dignified and democratic.

Despite multiple renovations, the library has retained nearly all of its original interior features. The 1990s restoration project focused on structural reinforcement and accessibility upgrades — never compromising the historic fabric. The building was listed on the National Register in 1977 and remains one of the most architecturally intact Carnegie libraries in the region.

For lovers of civic architecture, this is a rare example of a public institution that has never abandoned its original design ethos. The library continues to serve as both a working space and a monument — a place where architecture and public service are inseparable.

7. The Mutual of Omaha Headquarters (One Pacific Place)

Completed in 1970, One Pacific Place — the headquarters of Mutual of Omaha — is a landmark of corporate modernism in the Midwest. Designed by the internationally acclaimed firm of Skidmore, Owings & Merrill (SOM), the 22-story tower features a sleek glass and aluminum curtain wall, a signature of mid-century corporate architecture.

Its most distinctive feature is the inverted pyramid crown — a structural and aesthetic innovation that reduces wind load while creating a striking silhouette against the Omaha skyline. The building’s plaza, with its reflective pool and minimalist landscaping, was designed to provide a serene counterpoint to the urban environment.

Unlike many corporate towers of the era that were stripped of detail, One Pacific Place retains its original materials and design intent. The interior lobbies feature Italian marble, bronze trim, and custom lighting fixtures — all preserved through decades of corporate growth. The building was recognized by the AIA in 1971 as one of the nation’s top ten new office buildings.

For architecture enthusiasts interested in the evolution of corporate identity, this building offers a window into how American businesses used architecture to project stability, innovation, and permanence during the postwar boom. It remains a working headquarters — not a museum — making its preservation even more remarkable.

8. The Omaha Club (Formerly the Omaha Athletic Club)

Established in 1884, the Omaha Club building — completed in 1915 — is a rare surviving example of Gilded Age private club architecture in the Midwest. Designed by local architect Thomas Rogers Kimball in the Italian Renaissance style, the building features rusticated stonework, arched windows, and a grand central staircase lined with carved oak balusters.

Inside, the library and dining rooms retain original fireplaces, coffered ceilings, and hand-painted murals. The building’s ballroom, with its sprung hardwood floor and ornate ceiling medallions, hosted generations of civic leaders, artists, and entrepreneurs. Unlike many private clubs that have closed or been converted, the Omaha Club remains active — and fiercely protective of its architectural heritage.

Its preservation is due in large part to its continuous use. The building was listed on the National Register in 1973, and all renovations have followed strict historic guidelines. Even modern HVAC and electrical systems were carefully concealed to avoid altering the historic fabric.

For lovers of social architecture — spaces designed to reflect status, community, and tradition — the Omaha Club is a living artifact. It’s not just a building; it’s a social document carved in stone and wood.

9. The Miller Park Pavilion

Located in the heart of Omaha’s Miller Park, this small but exquisite pavilion was designed in 1910 by the renowned landscape architect Horace W.S. Cleveland. Though often overlooked, the pavilion is a gem of early 20th-century park architecture. Its hexagonal form, timber frame, and stone foundation reflect the Arts and Crafts movement’s emphasis on handcrafted materials and harmony with nature.

The pavilion was originally built as a rest stop for park visitors and features original wrought-iron benches and a copper roof that has developed a soft green patina over time. Unlike many public structures of the era, it was never electrified or modernized — preserving its original character as a place of quiet retreat.

Restored in 2005 using period-appropriate materials and techniques, the pavilion now serves as a venue for small cultural events — but its design remains untouched. The surrounding landscape, also designed by Cleveland, includes native plantings and winding paths that echo the pavilion’s organic form.

For architecture lovers who appreciate subtlety over spectacle, the Miller Park Pavilion offers a profound lesson in restraint, material honesty, and integration with the natural world. It’s a quiet counterpoint to Omaha’s grander monuments — and all the more powerful for it.

10. The Siena Hotel (formerly the Siena Apartments)

Completed in 1927, the Siena Hotel is one of Omaha’s most elegant examples of Mediterranean Revival architecture. Designed by local architect John Latenser, Sr., the building features stucco walls, red tile roofing, arched loggias, and wrought-iron balconies — all inspired by Italian villas of the Renaissance.

Its most distinctive element is the central tower, crowned with a bell-shaped dome and decorated with ceramic tiles imported from Spain. The interior lobby retains original mosaic floors, carved wood paneling, and a grand staircase with wrought-iron railings. The building was originally marketed as “a palace for the middle class” — a rare attempt to bring European elegance to middle-income urban living.

After decades of decline, the building was restored in the early 2000s by a private developer committed to historic preservation. All original finishes were retained or replicated using traditional methods. The Siena now operates as a boutique hotel — but its architectural soul remains intact.

For lovers of eclectic styles and social history, the Siena offers a fascinating glimpse into how architectural fashion influenced everyday life. It’s not just a hotel — it’s a cultural statement about aspiration, taste, and the desire to bring beauty into the urban fabric.

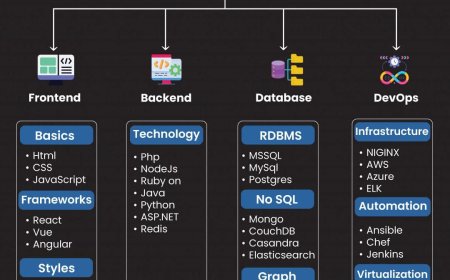

Comparison Table

| Location | Architectural Style | Year Completed | Architect | Historic Designation | Public Access | Architectural Significance |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Joslyn Art Museum | Neoclassical | 1931 | John Russell Pope | National Register of Historic Places | Open daily | One of the finest Neoclassical buildings in the Great Plains; designed by architect of the Jefferson Memorial. |

| Durham Museum (Union Station) | Art Deco / Streamline Moderne | 1931 | Graham, Anderson, Probst & White | National Register of Historic Places | Open daily | One of the largest and most intact railroad stations in the U.S.; exceptional interior detailing. |

| Creighton University Main Campus | Romanesque Revival / Mid-Century Modern | 1892 / 1968 | Thomas Rogers Kimball / Anderson & Gumpert | Local landmark; multiple buildings listed | Open to public | Unique campus-wide evolution of architectural styles over 80 years. |

| Omaha National Bank Building | Chicago School | 1917 | Holabird & Roche | National Register of Historic Places | Private offices, lobby accessible | One of Omaha’s first steel-frame skyscrapers; exemplary early commercial design. |

| Bemis Center for Contemporary Arts | Industrial Adaptive Reuse | 1920s / Reopened 1980s | Local architects and artists | Local landmark | Open daily | Model for post-industrial revitalization; celebrated by AIA for preservation excellence. |

| Omaha Public Library (Downtown) | Beaux-Arts | 1921 | Carrère and Hastings | National Register of Historic Places | Open daily | One of the most intact Carnegie libraries; designed by architects of the NYPL. |

| Mutual of Omaha Headquarters | Corporate Modernism | 1970 | Skidmore, Owings & Merrill (SOM) | Local landmark | Public lobby accessible | Iconic corporate tower with inverted pyramid crown; nationally recognized upon completion. |

| Omaha Club | Italian Renaissance | 1915 | Thomas Rogers Kimball | National Register of Historic Places | Private club; limited public tours | Rare surviving Gilded Age private club; exceptional interior craftsmanship. |

| Miller Park Pavilion | Arts and Crafts | 1910 | Horace W.S. Cleveland | Local landmark | Open daily | Exemplary small-scale public structure; harmonizes with landscape; untouched by modernization. |

| Siena Hotel | Mediterranean Revival | 1927 | John Latenser, Sr. | Local landmark | Hotel; public areas accessible | Unique urban expression of European design for middle-class housing; exceptional exterior detailing. |

FAQs

Are these sites accessible to the public?

Yes. All ten locations are open to the public during regular business hours. Some, like the Omaha Club, are private members-only facilities but offer scheduled public tours or events. Others, like the Joslyn Art Museum and Durham Museum, have free or low-cost admission. Always check the official website for current hours and any special access requirements.

Why aren’t there more modern buildings on this list?

This list prioritizes buildings with proven historical significance, architectural integrity, and enduring public value. While Omaha has many contemporary structures, few have yet achieved the level of recognition, preservation, and scholarly attention required for inclusion. The list reflects a 100-year span of architecture — a timeframe that allows for proper evaluation of a building’s lasting impact.

How were these sites chosen?

Each site was selected based on three criteria: (1) documented architectural merit verified by academic or institutional sources, (2) preservation status and adherence to historic standards, and (3) public accessibility and interpretive resources. Sites were cross-referenced with the National Register of Historic Places, AIA Nebraska archives, and local historical societies.

Can I take guided tours of these locations?

Yes. The Joslyn Art Museum, Durham Museum, Omaha Public Library, and Creighton University offer regular guided architecture tours. The Bemis Center and Siena Hotel provide self-guided interpretive materials. For private sites like the Omaha Club, contact their office for tour availability. Many locations also offer downloadable walking tour maps.

Is Omaha’s architecture under threat?

Some structures face pressures from development, but the sites on this list are among the most protected in the city. The Joslyn, Durham Museum, and Omaha Public Library are federally listed and legally protected. Others, like the Siena Hotel and Bemis Center, were saved by community advocacy and are now managed by preservation-minded organizations. Continued public engagement is vital to their survival.

Are there any free architecture tours in Omaha?

Yes. The Omaha Public Library offers monthly “Architectural Walks” led by local historians. The Durham Museum includes free access to its architectural exhibits with admission. Creighton University offers free campus architecture tours on select weekends. The Bemis Center also hosts free public talks on adaptive reuse and design.

What makes Omaha’s architecture unique compared to other Midwestern cities?

Omaha’s architecture reflects its role as a transportation and commercial hub in the 19th and early 20th centuries. The city boasts an unusually high concentration of Beaux-Arts, Art Deco, and early skyscrapers — many designed by nationally renowned firms. Unlike cities that underwent massive demolition in the 1960s, Omaha preserved a surprising number of its historic structures, creating a layered, authentic urban fabric.

Can students or researchers access architectural records for these buildings?

Yes. The University of Nebraska at Omaha’s Archives & Special Collections holds original blueprints, photographs, and correspondence for many of these buildings. The Joslyn Art Museum’s research library and the Douglas County Historical Society also maintain extensive archives. Access is typically free and open to the public by appointment.

Conclusion

Omaha’s architectural landscape is not defined by grandeur alone — but by authenticity. These ten sites represent more than aesthetics; they are physical manifestations of ambition, craftsmanship, and civic pride. Each one has survived economic shifts, changing tastes, and urban pressures — not by accident, but through deliberate stewardship.

For the architecture lover, trust is not given — it is earned. These ten locations have earned it through decades of preservation, scholarly recognition, and public engagement. They are not curated for likes or photos. They are preserved for understanding.

Whether you’re drawn to the marble halls of the Joslyn, the industrial soul of the Bemis Center, or the quiet dignity of the Miller Park Pavilion, each site invites you to pause — to look closely, to read the details, to appreciate the intention behind every brick, beam, and balustrade.

Omaha may not be New York or Chicago, but its architecture tells a quieter, more profound story: one of resilience, care, and enduring beauty. Visit these places not as a tourist, but as a witness. Let them speak. And listen.